Chapter One.

The Dry Water

The secret rivulet had vanished, the trickle of water that anchored their conspiracy to strike it rich and pay off their debts. Without irrigation, there was no crop. This

desolate arroyo in the Anza-Borrego Desert, Luis Mata’s promised oasis, was a gouged scar in the gravel and sand.

“The stream’s here—got to be,” Mata insisted, testing the dry creek bed with a bayonet. “The water’s underground, hiding close by. An earthquake shifted the flow. This rift zone fractures all the time.”

Silence dinned in the glare, profound as the vacuum on the planet Mars. Their starship had crash landed and there was nothing to drink. These badlands had canceled their scheme to coax prime cannabis to grow, concealed in the middle of nowhere. Back in the city, a pound of trimmed buds sold for four-thousand dollars. One ounce cost three-

fifty cash per cellophane baggie—all buds, no shake. Mata kept a coded ledger that listed prospective buyers and dollar amounts. There were enough eager customers to move kilo bricks of quality smoke, more than four porters or “mules” could transport on foot over the mountains to the west.

Jena Estery shook off her backpack and sighed, after their long trek through the sierras. In front of her loomed a streak of baked mud, flecked with iron pyrite and mica. “Without water, we farm prickly pear and sagebrush,” she said to the three men, pointing to a stand of drought-withered nopal cactus. “How do I salvage my inheritance, when my dear sister Lynn is a cash-only woman. Already, she’s moved her son Richard in to our parents’ vacant house.”

HO ‘alu Pakua, the Hawaiian boatman and navigator nicknamed Pak, offered Jena his last canteen. She took a sip, thanked him and handed it back. Pak’s face was brick red from the heat, the color of his bristly ehu hair. He pointed to a rockfall close by that had plummeted from the sheer cliffs. “Back home in Ka’u,” he recalled, “when the

ground shakes, beware of Pele, the Volcano Goddess. We steer the canoes for deep

water.”

“Maybe Pele hitched a ride with us,” Jena suggested, “she and the demigod

Kamapua’a, the Boar Boy. The Volcano Goddess and the Boar Boy,” she eyed Mata. “Those two divas like to screw people around.”

The ex-soldier mopped his brow with his boonie field-cap. What could he do? His three recruits were ready to turn around and abandon all hope.

“Full gallons a minute,” the ex-Marine muttered, as he sheathed his K-Bar knife,”flowing right down this draw.” Even in mid-summer at one-hundred and fifteen, when heat cooks these rocks. Purling like redemption out of split granite, right there by thosefan palms.

No one had been with him the year before when a ribbon of cold mountain runoff had flowed through this hidden spot. That thin source of irrigation grew a small crop of sinsemilla that he tended for months by himself, right up to harvest. He had toted back to the city one full duffel bag of manicured treasure that sold for top price in a few weeks.

The seedless buds, sticky as pine tar, crammed the stems—the pungent scent barked the lungs. Yet, Mata stayed under the radar, selling to people who smoked in the closet. Licensed dealers have to register with the government.

“Our money just floated away,” Jena drawled. “Salvation’s expensive on credit.” “Blood money,” agreed Pak.

“I’m here farming chronic to save Ettaleen’s ranch,” Mata reminded the pair.

“Pay off that bank loan or she loses her home. As for Pak? Mata held up a “V” for point two as he counted on his fingers. “Pak’s grandmother entrusted her land to him. Emma made him heir and executor. Now that she’s passed, the family expects a quick sale, no matter the buyer.”

“Don’t forget Sinom,” Pak chimed in, “he owes big hospital bills. Remember our wager,” he pointed to the detail-man.

“If I prove my worth,” Sinom spoke up, “then I become a partner, not just the hired hand. Bail us out of trouble three times and I share the profits. That’s the bet we made.

Jena and Pak nodded. That agreement was the reason that they signed aboard with Mata. The best deal that the veteran would offer the convalescent, whose actual name was Anthony Collins Mejia, was to bring him along for the small tasks, such as minding leaks in the drip irrigation, digging holes for latrines and composting rubbish, clearing vegetation to prevent wildfires, and picking up the trash. Only if Sinom proved himself, was he an equal.

Making big money was not the incentive for the couple, not growing marijuana. The detail-man was. Sinom wasn’t a charity case or a malingerer. Mister Mejia’s head wound had almost killed him. Recovering from the massacre at the local university took months. Which was why Pak and Jena took up his care.

Right then beside the missing stream, with all eyes on the younger man, Mata

seized the moment. “All right, shipmates, Our mascot here needs to settle up with his

doctors. Make his day. Form a skirmish line across that dry channel and find one AWOL creek! No one gets paid for their looks.”

“When I glance in a mirror,” Sinom responded, “nothing’s familiar. There’s a

mouth, a nose—a face. But who is that person? The facts I have. . . but not conviction.”

“The condition’s point zero,” Mata scoffed, tapping his own chest. “Welcome aboard, sailor! That SWAT team saw an indian and shot first. You freckle in the sun, but you’re not white enough to pass.”

“Don’t bully him, Mata,” Jena intervened. “Negotiating identity is not common sense. You’re Latino, honorably discharged, three years of college, mas o menos. For all that, Remember being homeless?”

“I’m not faulting anyone,” Mata replied, self conscious about his Spanish. “Not with my resume. But our life support just failed and the starship’s adrift.” he said, eyeing the dry water. “And I’m in charge, more or less.”

Now, Mata had led a squad at Falluja where his Marines fought house to house. Every grunt made it back, despite the collateral damage. And Pak had crossed the Pacific alone in a sailboat, the same thirty-footer where he and Jena lived on board, along with Sinom. As for Ms. Jena Estery, No one lives off the land better than she does. Her

parents were park rangers who taught her how to survive on roots and berries. And Jena’s a teacher to boot. Always on about ideas and how people think.

2

“Now tell me again why Sinom’s embedded with us?” Mata challenged his team.

“Hana hou, all you haoles, mind the canoe,” Pak called out to the crew from the empty creek bed where luck once flowed. “Find water or die, people. Politics later!” And the Islander danced a hula that his tutu Emma had taught him when he was a kid, a barefooted keiki big for his age. As Ho ‘alu Pakua swayed right then left, he sang an old mele from the days of the sugar plantations. “Manuela Boy, my deah boy. . . no more five-cents, no more house, go sleep A ‘ala Park with the homeless.”

The message was plain, Pak’s pidgin English: Pull together or drown, folk. Rig a new heading. Don’t jettison the seeds. Get out of yourself. Stand as a crew.

Ho ‘oponopono was the way to survive: the wayfaring way. Make ready the sails!

The Islander’s call to sit together in counsel cut the leader a break. Mata sipped some water, as the crew rallied and set down their backpacks. Using their walking sticks, they searched for snakes, scorpions and stinging harvester ants that leave telltale nests. All that was left of the underground colonies was the scorched husks of seeds at the

tunnels. Rabbit and spider burrows were empty, nothing in the dens.

So, on a dessicated riparian stream bank that was now half of zilch, three partners and the longshot, Jena, Pak and Mata, along with Sinom, sheltered under a rare desert willow whose roots pierce eighty feet down. They took a breath and cleared their

thoughts.

Mata unloaded the M1 carbine, and once the weapon was clear, propped the

vintage battle rifle against the knarled trunk of the solitary tree. The compact barrel was perfect for tight quarters on the trail and passed for a deer rifle. If they were spotted by hunters or backpackers or worse, the thirty caliber frame, designed during World War Two for cooks and combat engineers, wouldn’t give them away like a modern AK 47 assault rifle or a computer-designed AR 15 combat Armalite, which were Mata’s choice of firepower.

Mata’s own Smith and Wesson forty caliber pistol stayed in its holster, locked and loaded. Pak carried a forty-five Browning ACP handgun, as instructed, but tucked in the Hawaiian’s ukulele case with a box of mil-spec ammunition and five charged magazines, all supplied by the veteran. For Pak, guns were for provisioning meat. And at that

moment, finding water came before anything else.

A Santa Ana wind soughed through the deserted gully that was hemmed in by

sheer stratified scarps. The creek’s sintered mud bottom held the tracks of bighorn sheep, a few wild goats and a stray buck with a game leg. Some clumps of brittle reeds were cropped to the root, tough hollow stems tossed aside, discarded fodder. Entombed in the adobe were some mummified frogs, dragon flies and aquatic bugs.

A mountain lion had patrolled the cracked remains of the shrunken ponds.

There were no signs of people: no footprints, no litter, no trace of habitation, at least what they detected. But the Anza Borrego foothills are a crossing point for

contraband from Mexico and unauthorized immigrants seeking a fresh start or fleeing from civil strife. Armed traffickers and the drug cartels infiltrate the back country, in order to move their illicit cargo of drugs or people or money to be laundered. Bandits and vigilantes kidnap migrants for ransom.

The sun was arcing over the mountain pass that had brought Mata and his cohorts to this hidden slot canyon. Shadows lengthened in the furnace. Each of them carried three canteens per person and the last flasks sloshed as they mouthed a few drops.

3

Jena licked her lips, her eyes closed. “I was raised in a river delta, Miwok Indian country. My folks kept a small museum at their park-ranger station. Our home was

crammed with native artifacts: baskets, utensils, the stuff of daily life. Each year by the river, we prepared a feast that we collected from the delta and cooked ourselves as a

family, as had the Miwok. The finest Napa wine flows to the marshes, the fat cattails and crisp pickleweed. My sister hates the outdoors, especially with no cellphone reception. I wondered why our family camped like nomads, but I love the quiet.”

Pak swished a mouthful of liquid and bobbed his head at the peaks. “Relief is two thousand feet up where we found that small lake. Tall pines, a cool breeze, trout and bass even where fresh rain collects. From there, it’s a straight shot to earth,” he eyed Mata and shook his canteen. “I’m down to a quart.”

Jena opened her eyes and surveyed the salt foothills. “The rain shadow haunts a desert. Those crests behind us block the clouds. What little moisture flows in doesn’t go far.,,

“I won’t turn back,” Sinom declared, loud enough to echo. “Return to what, solitary confinement. A lab where I grease the equipment? I don’t own my labor.

Technology booms on campus. Money pours in. Me, I spin in circles, a windmill for hire. Maybe water’s close,” he scored the dry creek with his boot. “A long shot beatszero and being erased by default. I’ll drink spit while we search.”

“Hear him?” Mata recovered, after a moment. ‘Try’ is the word. And I have a gimme. A little way down this gulch, there’s a pond near where the creek dove underground before this stretch went missing. Let’s hike down slope to the sag, fill our canteens and regroup back here. We’ll dig up this streambed if we have to,” he speared the sand with his bayonet. “Hold on, Captain Cook,” Pak said, naming the first British seafarer who colonized Hawai’i. “`Go for broke,’ push ahead, you’re telling the natives; press your luck! Those cliffs overhead could collapse. Landslides mar the footing where we have to pass. Earthquakes shook loose most likely.”

“You’re a dancer, Pak,” answered Mata. “Hula through that pile of rubble. Bust a move for Sinom here. Steer through those reefs and salvage this mission. Make water happen.”

“That’s an asteroid belt,” Jena corrected. “And who says there’s water beyond?”

“Worried earthlings,” rejoined Mata, “This is Mars. We’re alone and out front. Defiance makes us immortal.”

“Pak, Jena,” Sinom pleaded, “Look who I am, Stuck in the copy machine.”

Pak glanced at Jena for a sign, kicked the dust and growled at Mata, “All right,

Captain America, sir, show us your mana, your mojo to make miracles happen. The Big Island kanakas mistook Captain Cook for their harvest god Lono, which proved dead wrong. They let the Englishman give the orders—for a while. The haole was delicious,” Pak flashed his teeth.

Jena grinned too.

“Sun’s going down,” Sinom exulted. “We should get moving.”

“Not you, mate,” Mata replied. “You stay behind and guard our gear and supplies.”

“I can keep up,” protested Sinom.

4

“You did fine on the trail.” Mata agreed. “But you’re bionic with that titanium plate patching your skull. Take a break. Once we refill our canteens, we’ll be back.”

Mata retrieved their two backpacks and led the way to a lookout crag close by.

Pak brought the M1 carbine that appeared small in his grip, as he and Jena

escorted their charge.

“How are you for water?” she asked the younger man. “One canteen left, three-quarters full.”

“Take mine,” she offered Sinom. “Pak and I can share.”

“Nah,” Sinom shrugged, “I’ll be in the shade.” Mata was measuring his every word, as the soldier searched the terrain. His watchtower nearby was a cluster of basalt monoliths with a clear line of sight west to the mountains and east to the minefield of boulders.

And once the four of them arrived at the fortress, Mata snaked through some

shadows to a hidden ledge where they unpacked their gear and stowed their supplies.

“Shouldn’t take long to the sag pond and back,” Mata tossed out, as if he believed it. “Pak will haul us up those pony walls; Jena knows where sweet water hides.”

Pak struck a wayfarer’s pose on the prow of a Polynesian voyaging canoe. Full sun notwithstanding, he pointed up at the ancestors’ star map for guidance and safe

passage. Instead of a seafaring canoe carrying seed plants to grow food and provide

shelter, like the ancients, this expedition was betting on a few magic beans.

But first, they had to find the sag pond and hump back the jugs.

Mata led Sinom away to a vantage point above the missing stream. “You can hear anyone coming before you catch them in sight. I’m leaving you the carbine—

Ettaleen and me showed you how use it back at the ranch.”

“This isn’t war,” Sinom answered.”

Mata snickered, “You called yourself a windmill, in front of the others. ‘Hell no, I won’t be blown down!’ So stand up and brace for the storm. There are no natives to carry the load. Just us.”

“I’m not a favorite, am I?” Sinom faced him. “Is it because I blank out and fall down sometimes?”

“This is Mars,” answered the ex-soldier. “Talking wastes air. The cotton comes first or we lose oxygen to breathe. We plant the flag here, or else.”

“Coming home a veteran has to be hard,” Sinom mused. “Marooned must be how it feels. After the shooting on campus, once I woke up, I’m in transit, always arriving.”

“Nothing’s wrong with me,” Mata grabbed Sinom’s empty canteens and clipped them to his utility belt. “Home ain’t home, never was, not for a military kid. My family never had a permanent address, just a domicile of record in Nebraska. Postings to Guam, Japan, Hawai’i, that’s where my old man was stationed overseas. Frontline garrisoned for the legions. He wore the uniform. We packed the belongings.

“When I turned eighteen, I had enough of Red Cloud, Nebraska and enlisted too. Went into the infantry. Semper Fi is the motto, Always Faithful: Unit first, the boots to your left and right, then God and country.”

Mata taped each canteen to his legs, one flask then the other. “In West Asia, we soldiers couldn’t tell the civilians from the enemy. Bad things happened. Plowshares we weren’t. Our recon squad had a saying about Lady Liberty, the statue in the harbor

5

holding a torch. Minding an empire loses the light, especially us grunts. And we had Ettaleen for a pilot, and a local interpreter to translate for us.

“So, Mister Mejia, let’s you and me smell our way to glory. For all the casualties.” Mata pivoted on his heel and left.

Sinom wondered why the ex-soldier had taped up the canteens like that. Then, he went outside and watched his companions enter the boulder field. The scene seemed crazy, absurd. Anyone growing chronic in the middle of the Sahara has to be brain

damaged, as Sinom was. And he thought, In order to get better, Sinom has to be bad. Worse yet, three other people were walking off the deep end: Mata, Pak and Jena.

Bright heat baked his skull; blood pulsed in his ears. And though nothing was there, something hummed in his ears. He staggered back to the protected high ledge and sat down on bare stone. In the blind shade, something bumped against his back, and when he felt what it was, he found Mata’s last canteen, which was almost full, stamped with the Marine Corps logo.

Grabbing the flask, Sinom rushed outside to call back the crew, but yelling wasn’t smart if intruders heard him. A tested soldier like Mata doesn’t forget his canteen. And if there was no sag pond, if that oasis had dried up too. . . The veteran was going for

broke. All or nothing, putting the others at risk. Or maybe they knew?

And Sinom recalled the rampaging graduate student at the college who killed

three people while taking an oral exam in order to complete his degree. After the SWAT team swarmed the building, they fired into the basement, assuming that Sinom was a

suspect. Sinom heard no warning. Words are not bullet proof. A medical helicopter

airlifted him to a trauma center in grave condition.

Sinom forgot his own name sometimes, which is what his alias sin nombre meant, “without a name”. Seizures upend experience. Someone who’s shot at a university and wakes up an epileptic doesn’t trust language. In front of him loomed the desert, stark and sere. Sounds echo, treble in the luminous expanse. The porous sand evokes infinity— and death. Not simply dry bones and bleached earth. But the way people are ciphers,

Cruel one moment, kind the next. All good or bad? Maybe not, but entangled and frail. Smiles seem a disguise. Learned concepts a mask. Who can be trusted? What is the key?

Just then, Sinom’s head wobbled on his neck, a current shot up his spine. He

swayed on his feet. And a shadow at first, the rainbow aura clouded his senses until

white light flashed, an electric hammer. He tumbled down and down, thumping against the embankment as he rolled off the grid.

He woke in a cactus patch, covered with blood and ants. Sweat stung an eye.

Down in the dust unable to move—that was the epilepsy. He managed to breathe, not by volition but instinct. Next to his face, ants were bringing up wet seeds from their burrows to dry in the heat. Which Sinom thought strange, since little rain had fallen in these long years of drought.

And then, after a moment, he was able to flex his wrists, roll on his back and feel blood staining his shirt. He was on a narrow rise above the dry creek bed, with beached river rocks below. The postictal stupor after the seizure blunted the panic, as if he were back in a skilled nursing facility drugged with morphine and atavan.

Cactus thorns had pierced his arms and flank. The blood stains, though, weren’t blood, because he tested the kool aid with his fingers. Sweet and acidic, The taste was familiar. At Ettaleen’s ranch, before the trek here to the desert, Jena had shown them a

6

patch of prickly pear where cochineal bugs, tiny insect parasites, fed on the pads of nopal and exuded a crimson ink.

Jena had recounted a vignette from the history of Alta California, which was part of New Spain. Part of her Miwok ancestry. A shipment of cochineal bugs was imported to San Francisco from Oaxaca, Mexico by a Franciscan priest. The padre’s plan was that the captive indios at the local mission settlements would produce barrels of carmine dye for export to Europe where bright vestments and cloaks were in vogue. The native

prisoners, though, died off too quick from measles and whooping cough to farm the

cactus insects and turn a profit.

You’re hallucinating, Sinom realized as he baked in the sun. Get in the shade.

Crawling uphill to the rock shelter, he slip-slid in the loose sand, mired. The dry creek below him gleamed, a bleached prehistoric spine. Thirst took over. He had to

move. Rolling sideways on the low embankment, one boot struck rock, lava most likely because it resembled petrified fossil molasses. And he noticed that the earth abutting the igneous stone dike was moist, and not from sweat. Why was it wet, Where was the leak?

“Mind your moon,” he had muttered to himself, “waxing and waning!”

He dug his boots into the lava ridge and began climbing to the watchtower

stronghold. “Oh, I brushed against some prickly pear,” he explained out loud, as if

defending himself from questions. “Stained my clothes,” he scrambled up. Once he

reached the the basalt monoliths, he retrieved Mata’s abandoned canteen and sat panting at dusk, “Gravity’s tricky, hereabouts.” He was okay plucking thorns from his chest.

Grace in motion.

Sundown was edging the tall crests. And limning the streaks of magenta and rose, strange noises droned near a curve of the creek bed, strangled peeping croaks that dotted a low earthen bank above the high water mark left from long-ago monsoon flashfloods. He grabbed his head. Was the bedlam there or not? Would he ever be other than

moonstruck? From his backpack, he grabbed a flashlight, not afraid of the wind-hurried shadows, almost. Exhausted as he was—the dark seemed a promise.

Jena was the one who located Sinom, after she and the others returned from the sag pond and found him missing. His tracks led over the edge of a bluff. He was

hunched over a deserted rabbit burrow dug into the creek bed, with a long hollow reed in his mouth.

“I know how this looks,” he squinted into their torches, and held out a small live frog.

Pak and Mata locked arms, ready to tackle him. “Hold back, you men!” Jena ordered.

“What have you got there, Sinom?” she asked.

“Wait,” he replied, shading his eyes. “Before you three hiked to the pond, Mata told Pak, Find water and salvage this mission, right? He did say that, ‘salvage the

mission’.”

Jena held out her arms and said, “Stop, listen to him.”

“Mata did say something like, save the mission,” Pak agreed, after a moment. His lips were dry and chapped. “But the pond’s too far away to irrigate the pakalolo seeds, though we topped off our canteens.” And Pak stamped his foot and groaned, “Auwe!

Right here, we need that missing stream. Right here.”

7

“Okay, cup your hands and step forward,” Sinom replied. Only Jena did as he

asked. And using the hollow reed like a laboratory pipette to measure and transfer liquid, Sinom dribbled gold into her palm. She smelled the sample and tasted her fingers.

“Water. . .?” she reacted and drank.

Sinom released the miniature frog and it hopped into the deserted rabbit lair. “Singing frogs in empty burrows. Ants drying wet seeds from their tunnels,” he marvelled. “Our water dowsers tapped the missing creek. Their nests flag the flow underground. I’ll show you where the stream went.”

“Stand down,” Mata ordered Sinom. “No falling off cliffs! It’s dark, morning’s the test.”

“Show us what you got, brah,” Pak countermanded the soldier. “Or I’m ready to bail from this valley of smoke.”

Sinom moved a few yards away to an ant nest to show them more proof And this time the Hawaiian held out his hand. “Wai,” Pak exclaimed, “coconut milk!” And he vamped round Sinom’s find singing in Hawaiian, “the rain lurking behind walls of stone,

ka ua pe’e pa pohaku.”

“Let’s not get ahead of ourselves,” Mata cautioned.

“Tune your ears,” Jena gestured at a knoll above the wandering stream bed.

“Water music broadcast live. Frogs, there and there and there. A good stretch. And thedamp ants besides. Verify all you want, Do the science!”

And several times in different spots, through the straw, Mata sucked up mouthfuls of moisture. Only then did he sit and switch off his flashlight. His throat was parched and he coughed. After a moment, though, his voice rose, “cool and fresh, good mountain ale. Question is, Enough for Mars?”

“I bet, yes,” replied Jena. “Tastes sweet, Clean runoff from the mountains.”

“Wai is the wager, oh chief,” Pak laughed, ‘ piliwaivvar . “Enough water to float the canoe, I risk my bones. Sinom hit paydirt! A comeback slakes a big thirst.”

“Did the detail-man crack his jinx?” Sinom ventured out loud. “Plan B is my religion! Two saves to go and we split the profits.”

“If the dry water’s there at first light, Semper Fi, we turn into farmers,” Mata

agreed. “There’s an irrigation pump stashed in a cave. Otherwise, there’s an all-terrain vehicle under wraps so that we can clear out fast.”

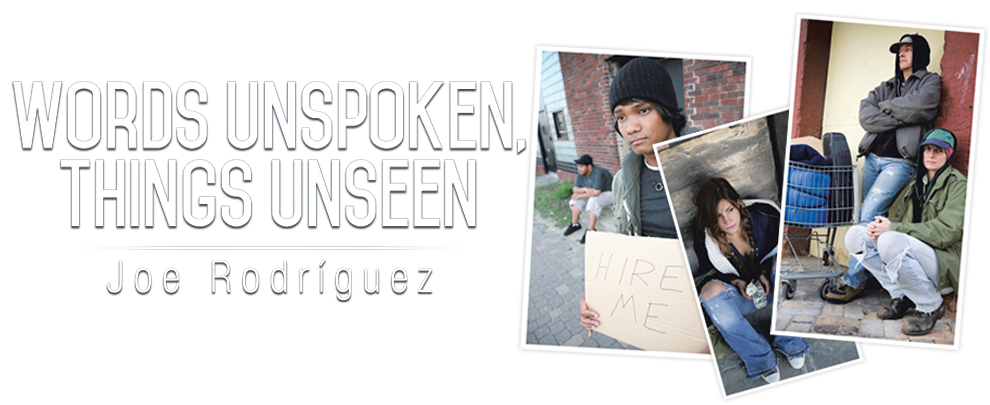

About the Author

Written by Joe Rodríguez

Joe Rodríguez is a novelist, literary critic, war veteran, licensed vocational nurse and university professor who once slept on a steam grate at the very college where he would later teach. Rodríguez served in Vietnam from 1965-1966 and earned his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from San Diego State University in 1967. He went on to earn his Ph.D. from the University of California, San Diego, in 1977, and he taught in the department of Mexican American studies at San Diego State University. Rodríguez is also the author of “Oddsplayer” – a novel about Latino, Anglo and African American soldiers in the Vietnam War – and he is currently in the process of publishing his third book, “Growing the American Way” – a novel about a group of people who grow marijuana in secret in the desert, make a small fortune and turn their lives around. He currently resides in San Diego. He can provide knowledgeable commentary on his creative writing process, his experience being homeless, his military service, issues affecting Latin American people in the U.S. and what it was like to grow up in a military family

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- chubby on L.A. is spending billions to fix homelessness. The problem is only getting worse

- https://pehrsilver.com on L.A. is spending billions to fix homelessness. The problem is only getting worse

- Silver Earrings For women online on L.A. is spending billions to fix homelessness. The problem is only getting worse

- Buy Silver Jewelry Online for women on L.A. is spending billions to fix homelessness. The problem is only getting worse

- Buy modern Silver Jewelry Online for Women in india on L.A. is spending billions to fix homelessness. The problem is only getting worse